I recently read and enjoyed Cody J. Shakespeare and Jason H. Steffen’s effervescent “Day and Night: Habitability of Tidally Locked Planets with Sporadic Rotation.” They explain that potentially habitable planets orbiting red dwarf stars would need to be close enough to their suns that tide locking—explanation here—would be inevitable. Red dwarfs being the most common type of stars, it follows that tide-locked worlds could be the most common variety of potentially habitable worlds. The traditional view is that libration aside, a tide-locked world’s orientation with respect to its sun would be very stable over long periods. Thus the old notion that all the volatiles would inevitably solidify and precipitate onto the forever night side (not actually the case, as even a thin atmosphere can transfer heat surprisingly well).

Shakespeare and Steffen’s model suggests that under certain conditions, tide-locked worlds can “flip,” reorienting themselves so that what was once in night is now in day, and what was formerly illuminated is now in shadow. This would be accompanied by extraordinary climate change. Even more impressively, it would occur over what are short time scales, even by human standards.

While this is terrible news for anyone living on a world orbiting a red dwarf—particularly if they don’t want to adapt their agriculture from Saharan heat to Antarctic cold overnight—this sort of process is a godsend for SF authors. All one needs to do is plant a human community on such a world (perhaps because the humans no longer believe in due diligence, because they were defrauded, or because they had no choice), orchestrate a flip and watch plot ensue. It practically writes itself. Or it will, once news of the paper percolates through the SF community.

While Shakespeare and Steffen’s scenario may be novel, SF writers have not disappointed when it comes to imagining scenarios that radically and rapidly alter a planet’s habitability. Consider these five classic works.

The Year When Stardust Fell by Raymond F. Jones (1958)

Earth has in recent history passed through cometary comas—several times—with negligible effect. Nevertheless, boy scientist Ken Maddox is inexplicably apprehensive. Rightly so, for the dust filtering down through Earth’s atmosphere is unlike any experienced since the rise of mechanized civilization.

Across Earth, adjacent metal parts fuse. Complex machinery stops functioning. Technological civilization halts. The formerly industrialized world faces famine and worse. Ken and his fellow scientists race to find a solution, but can they succeed before billions die? In a word, no.

This may sound very much like some modern SF works in which technology suddenly halts due to natural or magical phenomena and society collapses. Is it derivative? Note the date of publication: if there is influence, it is from Jones to the modern authors.

“Tindar-B” by Patrick G. Conner (Collected in Stellar #2, 1976)

The crew of the Bussard ramjet Plantation are the sort of enthusiastic explorers whose atmospheric test consists of cracking open the airlock to see if the planetary atmosphere kills them. Nevertheless, when there are some available records re: the obscure world of a G9-V star, Plantation’s crew does consult them. Alas, the three-hundred-year-old paper copy of a seven-hundred-year-old paper log1 entry is terse, smeared, and alarming:

“… from orbit. Ghastly. No survivors.”

The prudent course of action would be to take off before discovering firsthand what local peculiarity slaughtered the first explorers. As one might expect from the atmospheric test, the Plantation’s crew opt for the considerably bolder option of waiting to see what happens.

Yes, this story basically features that Galaxy Quest scene played completely straight. I assume starships are very cheap and crews abundant and expendable. Otherwise only cautious sorts would be chosen for the crew.

Hestia by C. J. Cherryh (1979)

Nattering nabobs of negativity warned Hestia’s human colonists that the valley selected was unsuitable for settlement. The settlers disregarded the advice. Disaster after disaster ensued, with the result that the tiny community is inexorably spiraling towards extinction.

The settlers are convinced a dam would solve all their problems. Sam Merrit, hired to construct said dam, is certain the colonists are deluding themselves. The settlers take steps to ensure Sam has no choice but to try. Unbeknownst to Sam or his employers: Hestia has natives whose territory will be flooded if the dam is built. The colonists’ foolish determination may well trigger interspecies war.

While the above may make it sound like the novel is short on sympathetic, sensible characters, that’s not true. Sam is reasonable enough and so is Sazhje, the alien Sam befriends. Unfortunately, policy decisions are made by self-deluded fools. There are no sequels to this novel that I know of, or we’d know if self-deluded fools were a self-solving problem.

Rocheworld by Robert Forward (1990)

Human explorers reach the Barnard’s Star system and discover a double planet in that star’s miniscule habitable zone.2 Eau is dominated by a water-ammonia ocean. Roche is an arid world. The close-orbiting pair is unlike anything in the Solar System.

Under the correct circumstances, a sea’s worth of water can transfer from Eau to Roche. While the implications of Eau and Roche’s proximity are lost on the explorers, Eau’s native species, the Flouwen, are intelligent, friendly, and eager to warn the humans about the impending natural disaster into which the explorers are sailing. But will the warning come in time to save the humans?

In most of Forward’s novels, prose and characterization rarely distract from the elegance of whatever scientific or technological wonder he wanted to showcase. In this case (or at least case of the edition I read3), he glanced at more character-driven matters; there is a passage towards the end of the book discussing why people might willingly embark on a one-way trip to another star system—a discussion that I still remember, decades later.

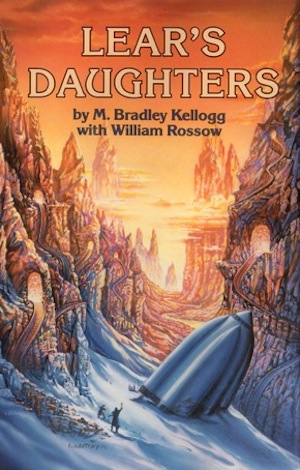

Lear’s Daughters by Marjorie B. Kellogg and William B. Rossow (2009)

Inexpensive faster-than-light travel has enabled humanity to strip-mine whole planets to feed the economy’s insatiable hunger. Next on the menu: the planet Fiix, some six hundred light-years from Earth. A routine exploratory mission is dispatched, no doubt to be followed in due course by an armada of mining machines.

Fiix is traversing the Coal Sack. Presumably this is why the planet is plagued with unpredictable weather and climate. The handful of native Sawl attribute the calamities to two warring goddesses, but surely this is but the irrational folklore of a people barely clinging to life on a hostile world. Or perhaps the Terrans have completely misunderstood Fiix’s situation and are about to undergo a memorable learning experience.

A detail that jumped out at me is that although Earth is chewing through planets at an impressive rate, most people on Earth seem to be abjectly poor. This suggests that Earth has a high Gini Coefficient (the measure of the efficiency with which wealth is redirected from the undeserving many to the deserving few), probably even higher than any modern nation’s. Who says there can’t be progress?

***

Endangering characters with heretofore overlooked or underappreciated natural phenomena is an abundantly plot-friendly concept. Examples abound, of which the five above are but a very small sample. I didn’t even touch on supernova, interstellar dust clouds, or abrupt ocean decarbonization! Feel free to mention other such works in the comment section.

In the words of fanfiction author Musty181, four-time Hugo finalist, prolific book reviewer, and perennial Darwin Award nominee James Davis Nicoll “looks like a default mii with glasses.” His work has appeared in Interzone, Publishers Weekly and Romantic Times as well as on his own websites, James Nicoll Reviews (where he is assisted by editor Karen Lofstrom and web person Adrienne L. Travis) and the 2021, 2022, and 2023 Aurora Award finalist Young People Read Old SFF (where he is assisted by web person Adrienne L. Travis). His Patreon can be found here.

[1]The author explains why the records are on paper and not, say, microfilm.

[2]In one of those coincidences that plague SF, both Forward and Charles Sheffield managed to independently, simultaneously write stories about close-orbiting binary planets.

[3]I should note that publication dates can be tricky. A version of “Rocheworld” was serialized in 1981. A different version was released as “The Flight of the Dragonfly” in 1984. A longer version of “Flight” was released in 1985. Finally, the latest, longest, retitled version, was published in 1990.

According to one of Niven’s Draco Tavern stories, the chirpsithtra live on tide-locked worlds around red dwarf stars. But presumably they have learned to cope with the sudden reversals over the last billion or so years.

I absolutely love Nightfall (the expanded coauthored version), which may not fit your criteria here?

Its a great story of the end of the world, and a rebuilding

In Deepsix, Jack McDevitt takes the simple expedient of running the planet into a gas giant. Of course, humans need to explore the planet before it is destroyed. And the planet is already experiencing catastrophic quakes.

I’m wondering if Harry Harrison’s Deathworld would count.

The Brothers Hildebrandt were notable illustrators once. I had a picture-book of covers & posters. The cover of Stellar 2 above was in there, & I’d always wondered where it appeared.

wrt interstaller dust clouds, Hoyle’s The Black Cloud would turn out to be a disaster rather than a couple of harsh seasons if a scientist hadn’t figured how to communicate with the cloud. (Sentience was obvious: it shot off mass to slow down as it approached the sun before wrapping around it like a traveling Dyson sphere. Communication was harder.)

In Cowper’s The Twilight of Briareus, a supernova turns random people into erratic telepaths, stimulates an immune response that shuts down most women’s reproductive systems, and for lagniappe chills Earth enough that the south of England resembles Greenland.

Note that Galaxy Quest … borrowed/diluted … the scene you link to; Flesh Gordon did it decades before, although Tony Shalhoub was a hair more cautious than Dr. Jerkov.

Egan’s Diaspora has a gamma ray burst as the reason why humans are all computer programs now rather than having robot bodies. That’s not the only reason I think it’s a spectacular sense-of-wonder sf novel.

@5: Specifically, that’s illustrating “Custom Fitting”, the only Hugo nominee James White wrote in a quietly distinguished career; it draws on his decades at a tailoring firm.

Can someone help me? I have a YASID situation. I have vague recollections of a giant conference of very serious astrophysicist and meteorologists and political leaders all discussing what to do when the Earth orbits into the vast trailing tail of a passing comet, resulting in extra elements becoming water vapor in our atmosphere, causing a predicted 300+ years of steady rainfall, forcing humankind to improvise enormous floating city-states that can survive, drifting atop the new global ocean.

Ring any bells, anyone?

How about Jack Williamson’s Born of the Sun? Whatcha gonna do when you realise the planet under your feet is… hatching?

Second Ending also was a Hugo finalist, wasn’t it?

I read The Year When Stardust Fell back in 1969, out of my grade school library when I was in sixth grade. I depressed the hell out of me back then, but the story stuck in my mind for nearly five decades, even when not remembering the title of author. About five years ago I somehow tracked down the title and ordered the paperback reprint from Amazon. Even rereading it made me feel that depression again, even with all the technological advancements our world has been through since the time it was first published.

@10 The same issue drives the Marvel Eternals film.

@11: that will teach me to rely on aging memory rather than the net; When The White Papers was being put together, somebody said “Custom Fitting” was his only nominee — and I never checked backwards. He was also nominated the year after The White Papers was published, for “Un-Birthday Boy”, and actually co-won a Retro-Hugo (and had four assorted nominations), although those were in the collective categories (best fan writer/artist/zine), which IMO are … difficult … to judge fairly.

…and nobody’s mentioned When Worlds Collide?

I’m shocked, I tell you. Shocked.

I mean, what bigger planetary disaster could there be than having your planet smacked into oblivion by a wandering gas giant…?

Lack of due diligence seems to be a major failing of starship crews and colonists to far distant planets during the 1950s and into, at least, the 1990s, possibly following from the logic of anti-regulation folks who believe that health and safety procedures are for stupid, cowardly losers who would be staying home taking advantage of bread and circuses[1]. It’s interesting that only Mr

Some specifics:

@1 (Dan Blum): iirc, the Chirpsithtra live on paired, tidally-locks worlds, which are quite rare. Since it’s been quite a while since I read anything by Niven, I may be wrongly recalling this. I’m not sure if pairs of tidally locked planets in the habitable zones around M-dwarfs are stable (and don’t feel like trying to do the math :-( ).

@2 (Jer): This is certainly one that’s both unpreventable and doesn’t necessitate particularly stupid starship crews or rape-and-burn capitalist economies.

@@.-@ (PamAdams): I think it’s interesting that the successful conclusion in Deathworld, thanks to Jason DinAlt, was pretty much the exact opposite to the method of the colonists in Legacy of Heorot. One wonders how Harrison got published.

Intrepid spacefarers have been testing alien atmosphere by the “{sniff} Smells OK to me” method a good deal more recently than the 90s – I’m thinking of Another Life, a Netflix series of interest to, well, people like me. The crew of (apparently) Earth’s only interstellar spacecraft in this one are, well, manifestly not risk-averse. Their venture into breathing unfamiliar air led, sadly, to their infection by an alien virus which built proteins out of iron and boron (regrettably, the show neglected to describe how), which had the distressing effect of making one unhappy sufferer’s spinal cord leap out of the back of her neck. But our bold crew were not discouraged! In a later episode, with the ship running low on supplies (they were down to their last 25 kilos of quinoa, so the situation was clearly urgent), they set down on a handy planet and not only didn’t bother testing the air, but started scarfing down the native vegetation without a moment’s delay. Which proved an excellent way to discover that the stuff was loaded with hallucinogens… The ship had a decontamination chamber, where people would wait before a little sign lit up green with a “Decontamination Complete” message. These and other incidents convinced me that lighting up a little sign was the only thing the decontamination chamber did.

Ahem. Yes. Actual subject of the item…. A couple of fairly subtle examples sprang to my mind, with closely related themes. One was the planet in Poul Anderson’s Let the Spacemen Beware! – also known as The Night Face – where the human colonists developed a rather distressing reaction to some of the native flora; the other was the planet Dendra in Brian Stableford’s Critical Threshold (second in the “Daedalus Mission” series, where the starship Daedalus sets out on a mission to recontact Earth colonies left neglected for eighty years, and find out what’s gone horribly wrong with them.) Dendra has no axial tilt worth speaking of, and consequently no seasons… which means that what would be seasonal events on Earth are localized and unpredictable on Dendra… which turns out to be bad news when the human colony happens to be the site of the grand mating dance of the hallucinogen-emitting butterflies. (Hallucinogens are wonderful for things like this, because they don’t involve expensive special effects sequences the way exploding planets do; a few distortion effects and coloured filters on the camera lens, and some prog rock on the soundtrack, and you’re done.)

At least for the Daedelus missions, the results of settling alien worlds with insufficient information and support were only unpleasant. The previous survey mission only found the remains of extinct colonies.

What, is nobody going to mention SevenEves?

Understandable.

The back story calamity in the webcomic “What it Takes” evidently involved a pole shift- not a magnetic one, but rotational. Maybe. The survivors are less concerned with discussing the cause of the disaster than they are determining who needs to be killed to restart civilization.

@16 – No, it was another species who lived on paired worlds (per “Grammar Lesson”).

Piper’s Four-Day Planet

Thinking about double planets reminded me of Homer Eon Flint’s 1921 novella “The Devolutionist”. Except that those two planets were attached at the poles and had a common axis.

In “Legacy of Heorot” the colonists wipe out the local apex predator, only to discover that the native fish are a juvenile stage of the apex predator, kept in check by the cannibalistic tendencies of the apex predator. Once there aren’t any more apex predators all the juveniles grow up. Simultaneously. And there’s the colony, just full of tasty humans.

It’s a bit less full of tasty crunchy humans by the end of the book.

There’s Ministry for the Future by Kim Stanley Robinson, but as it deals with the effects of climate change in 5-10 years time, it’s unfortunately a lot less fictional than most of the examples on this list. Termination Shock by Neal Stephenson came out around the same time, and deals with similar issues in a more positive way.

Poul Anderson’s BRAIN WAVE is sort of the flip side of planetary disaster (although it is a disaster for many people).

@26: I was wondering about including that — especially since Anderson gives only guesses of what might have happened when Earth entered the region of slow thought.

Going for the very obscure: the late Mark Keller responded to a parent’s complaint that Kzin were impossible (males with hair-trigger tempers and non-sentient females don’t produce sentient survivors, although posters elsewhere tell me Niven later handwaved that) with a scenario for a planet where an infection responds to a certain concentration of estrogens, such that there are no sane adult women and girls know what they’re facing. (People who know people with fanzine collections might find this in Proper Boskonian — but note that it doesn’t come with the trigger warning that it should have, as it was written 45-50 years ago.) It’s possible he had read J. T. McIntosh’s “First Lady” (men have shown that a new world is survivable, now escorts (who know the odds) are bringing someone to find out whether children are plausible); I emphatically don’t recommend this story, as McIntosh was very much of his time (1950’s).

@24 – You really can’t expect Niven/Pournelle protagonists to know anything about ecology or see the necessity of finding out in advance what lives in the area they’re planning to colonize.

@28: They did deliberately choose an island to limit the complexity of the problem they were facing with the unfamiliar environment, but a separate problem limited their ability to learn as quickly as needed about the ecology.

I have to bring up Anne McCaffrey’s Dragonsdawn, in which she expanded on the brief description in the prologues of her previous books in the Dragonriders of Pern series: colonists on a remote planet find themselves threatened by a deadly rain of spores from a wandering planet. They have no way to leave, but are able to genetically engineer small native avians into large “dragons”, which can burn the spores in the air before they reach the ground.

@19. Raskos: you mean the one with a Hillary Clinton analogue who makes sure she’s one of the survivors of the apocalypse, then shoots holes in the ISS module with a handgun?

Or the Jeff Bezos analogue who becomes a hero by saving the ISS with a private rocket?

Or the survivalist types who live 5,000 years underground and emerge exactly the same as the first generation?

@31 – All of those. Especially the last. Blowing their own glass lightbulbs for five millennia. Unaffected by genetic drift. Speaking unaltered 21st-Century American English. Oy.

But you forgot the survivors who made it through the bombardment in submarines and went on to evolve into seal people (sort of), with nobody noticing that they were swimming about in Earth’s oceans (presumably heat-sterilized by the bombardment) for 5,000 year either.

@32. Raskos: I didn’t forget. There’s only so much lunacy I can list… :)

There’s also the neo-Lamarckian ideas about evolution: a character from one of the seven genetic lines evolves to a 2.0 form and later a 3.0 version within her own lifetime simply by deciding to do so.

There’s the electronic devices that can only hold one text file at a time. If you finish an e-book you have to delete it to make room for a new one. Why? Because the journalist on the ISS had a laptop full of porn and the Seven Eves decide he shirked his duty because of it. Therefore, no personal devices will have adequate storage even 5000 years in the future.

This is either puritanical, another retro idea going back to the dawn of computing, or the driest humor in the history of the world (and I don’t find Stephenson funny).

There are many howlers in this one.

The Acknowledgements explaining that Seveneves started as a background for a proposed computer game felt like it explained a lot of the odd aspects of the future. (Two factions, discrete character types with different but more or less balanced competences and powers, etc.) Even the weirdness with computer storage and limiting to wired networking (while also having autonomous robots with much more computing power) might have been there to justify a game mechanic.

Granted, even if that’s the case, there’d have been an argument for recasting things more once the game was tabled and Stephenson decided to turn it into a novel.

Cat’s Cradle by Kurt Vonnegut

H’mmm.

Or Wolfe’s “New Sun,” where Urth is slowly being chilled because of a (black hole?) deliberately put into the Sun as punishment for human behavior; the purpose of the New Sun is to bring the “White Fountain” that will make the Sun shine bright again, but until that people have to cope with gradually receding insolation…global cooling sorta thing…

There’s also N. K. Jemisin’s Broken Earth trilogy.

@33 – I had expunged Stephenson’s ideas on evolution from my mind. Teaching the subject to undergrads provides enough occasions for despair as it is.

see also grrm’s Worlon, a deliberately chosen site for a humblebrag festival even though known to be only briefly habitably.

Last Policeman trilogy by Ben Winters – An asteroid is coming to hit Earth, but he’s still going to solve a murder. Brilliant as sci-fi and mystery….

I think Harrow the Ninth counts :)

@32 Raskos I can slightly get the retention of language, after all these communities have started very small and are slow growing, and importantly have zero outside influence.

Robert J. Sawyer’s Quintagio Ascension trilogy (Far-Seer, Fossil Hunter, and Foreigner) tell the story of a moon world that’s dangerously close to being destroyed by the gravity of the planet it orbits. The people know they only have a few hundred years until it happens, so they have to go from basically a Renaissance level of technology to space age in that amount of time. Wonderful books with wonderful characters, and a great storyline to boot!

@42: Language changes fast in small, isolated communities.

@30: There’s an idea for a future article: differing treatments of “Interstellar colonists plan to set up a low-tech paradise on a new planet and abruptly discover that their information was incomplete–but only after they have burned their bridges.” Besides McCaffrey’s Pern, there’s David Weber’s Grayson, which was settled after remote observation failed to detect that the lush, fertile world was awash in heavy metals. While the Graysons, like the Pernese, had been hoping to become farmers with airplanes, they instead started farming in orbital habitats–while stubbornly living on the surface. I’m sure there are more examples.

How about Lucifer’s Hammer by Larry Niven ?

“Supernova” by Poul Anderson is a fast tale about planetary-turned-interstellar disasters, despite the best (more or less) intentions:

https://s3.us-west-1.wasabisys.com/luminist/SF/AN/AN_1967_01.pdf

Ah, Seveneyes, where the invaluable orbital habitats don’t move above the crunchy bits of the moon * before* it become the Big Nasty Cloud…yeah, the stupid was strong in that, and that’s if you got beyond the 100k words of description before getting five page of plot.

Wow, a lot of hate for Seveneves.

OK, not to pile on, but it was far from my favorite Stephenson story, and I didn’t even pick up on most of the things people are pointing out.

What did stick out to me as oddly ill-thought-out: Apparently once the disaster happened, all belief in God went right out the window as a matter of course. (I don’t recall what gave me that impression, but a definite impression it was.) Because apparently clinging to theism is totally incompatible with a disaster that wipes out everything and everyone, saving only a tiny remnant.

Hello? The emergency space habs are called Arklets, collectively called the Cloud Ark. Did nobody (including Stephenson) recall where such a term came from?

My impression of Stephenson is that he is probably personally not religious, but not especially hostile to religion, nor ignorant of it, nor blind to its importance in many people’s lives, nor a fool. What was his thinking here?

Gotta mention C.J. Cherryh’s Forty Thousand in Gehenna. What if one side in a long-running interstellar war (the Alliance) abandons a colony, and the other side (the Union) rushes in, only to realize that it’s a colony designed to fail, and the Union just signed on to sunk cost on a planetary scale: a hostile climate that degrades technology, weird giant lizards who make even bigger earthwork spirals, and they won’t let minor inconveniences like buildings get in the way. The lesson is “adapt or die,” and the colonists (initially numbering 40,000) very nearly don’t make it.

@49. Stevo Darkly: “Wow, a lot of hate for Seveneves.”

I wouldn’t call it hate; I’d say disappointment. I wanted something immersive and well thought out. What I got was more of a headscratcher.

So much of it was a letdown, with many moments of just “Huh. That happened.” There’s an early part after the 5,000 year time jump that goes into some shadowy conspiracy that never materializes. It may have been just background worldbuilding for a video game, as someone said above, but it makes the novel seem incomplete despite its massive length and Stephenson’s wordiness.

@51 – Well put. When you look at the thought and work that went into Anathem, Seveneves was a real let-down.

When one’s novel begins with “the Moon blew up” and then never shares the cause of the Moon blowing up, it’s … fantasy, not science fiction, and if one wishes to write fantasy, write fantasy (elves, dragons, ghosts, oh my!) – it’s more entertaining that way.

53: Michael Reaves’ Shattered World is a bit like that, except it was the planet everyone lived on that got blowed up real good in a magical mishap. Luckily, the inhabitants had the tools needed to survive that error.

54; thanks. agree – the fantasy element of Seveneves was particularly weird given the (then) “near-future” setting, complete with pastiches of public figures that would have been expected at Baen.

Janet Kagan’s Mirabile, but the colonists brought the disaster, in the shape of hidden genes, with them.

53 is a fair point, but I think it was OK just to say “it blew up and no one on Earth knew why. Now we’re going to talk about what happened afterwards.” It’s a novel about the end of the world, not a novel about the quest to discover what made the moon blow up.

49: disasters far smaller than that have shaken people’s faith in God. Look at the Lisbon earthquake, for one famous example.

I was also disappointed in Seveneves (and in D.O.D.O. for that matter). I think a big reason why is that it was extremely gloomy. Now I think about it, it read more like a Stephen Baxter novel – big aerospace engineering projects, big disaster, most of the cast dies slowly and awfully. I wonder if that’s what he was going for?

Stephenson normally tends to be rather more optimistic.

The discussion seems to have taken a bit of a tangent; let’s get back to the topic at hand–thanks!

@50 Nit: Union and Alliance’s roles in 40K in Gehenna are reversed.

We later learn in Cyteen that there were deeper plans laid with respect to Gehenna by Union (or at least by Ari Emory) than were clear in the original book.

@45 I think all of Niven’s slowboat-settled colonies have the “learn about the planet’s sting in the tail after burning their bridges” element, but I’m not sure if any of them were intentionally low-tech.

Maybe Home in Protector, though in their case the unanticipated thing was a human Protector deciding to use their planetary population as the solution to a trolley problem.

57) sure, but that raises the question if whether in a story about an “unforseen planetary disaster” that is billed as science fiction, it’s really fair to the reader to posit a mystery and then a) don’t give enough clues for the reader to figure it out; or b) not explain the mystery along the way.

Everything from “The Red Plague” to “By the Rivers of Babylon” to “Earth Abides” to “On the Beach” explains what “it” was, although all four are much more focused on “what happens after” than the apocalyptic events; just seems like a cheat for an author who wants to be taken seriously to not give the reader something more than “magic.”

Especially given the rather ham-fisted nature of the leading characters in the set-up.

57) sure, but that raises the question if whether in a story about an “unforeseen planetary disaster” that is billed as science fiction, it’s really fair to the reader to posit a mystery and then a) don’t give enough clues for the reader to figure it out; or b) not explain the mystery along the way.

Stephenson does this occasionally with things that you’d expect to be a big part of the book, but which it isn’t actually critical to the plot to describe in detail. Snow Crash comes to mind: “After that it’s just a chase scene.” And The Confusion where you don’t get to see any of Rossignol’s adventures, you just see him writing a letter to the King in which he modestly refuses to describe any of them but just says something like “after my arrival, I saw to it that my servant was decently buried, my surviving horse stabled, my pitchfork wounds bandaged and my remaining clothes immediately burned”.